Ecological Tyranny: The Origins of Corruption and Environmental Degradation in Unrepresentative Raw Material Regimes

“Laws, like sausages, cease to inspire respect in proportion as we know how they are made.” --John Godfrey Saxe, American poet (1816 – 1887)

“Monsanto should not have to vouchsafe the safety of biotech food. Our interest is in selling as much of it as possible. Assuring its safety is the FDA’s job.” -- Phil Angell, Monsanto’s Director of Corporate Communications, New York Times, 10/25/98

'Tony Hayward, the beleaguered chief executive of BP, has claimed its oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is "relatively tiny" compared with the "very big ocean"'. "The Gulf of Mexico is a very big ocean. The amount of volume of oil and dispersant we are putting into it is tiny in relation to the total water volume." Hayward insisted that deep-water drilling would continue [to be an ecological tyranny over us all]..."

John Waythen, Hurricane Creek Riverkeeper with Waterkeeper Alliance: May 7th airplane flight footage over Gulf oil disaster area: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uG8JHSAVYT0 (5 min.)

The only comment I object to in Mr. Waythen's commentary is "We have to have fuel. We have to have gasoline." On the contrary, there are many options. We have gasoline because of a corrupt political regime that, in an ongoing manner, demotes other working options. Environmental degradation is a political regime, and thus requires political solutions.

To get to sustainability we are required to remove the corruption called an ecological tyranny. An ecological tyranny is a form of politics that enforces environmental degradation and protects it from being removed whether by politics or by market forces, respectively, by gatekeeping by corrupt politicians and gatekeeping by demoting consumer material and technological options. Currently, we live worldwide under informal ecological tyrannies that destroy our health, our ecologies, and our economies--and even destroy the corruptive frameworks of the politicians that protect them.

An ecological tyranny is an unrepresentative raw material regime. There are better ways. There can be representative raw material regimes, chosen by a more representative political process and more representative political institutions.

Continuing the theme of the previous post about extending checks and balances on power beyond the state institutions, what are the basic issues of degradative corruption that the bioregional state aims to solve?

The bioregional state aims to solve unrepresentative raw material regimes, substituting for them more representative raw material regimes. To do this, removal of forms of political gatekeeping is required. The environmental implications of political gatekeeping have material choice, technological choice, and environmental condition implications. Thus, such political gatekeeping can create an ecological tyranny.

There are two levels of ecological tyranny described below: the ecological tyranny of one raw material regime dominating all consumer choices in a category or its market, while demoting other frameworks toward sustainability politically; and the ecological tyranny of one raw material regime corrupting various forms of state politics, scientific workers, banks or financial lending institutions, and corporations into supporting an environmentally destructive flow and keeping out more sustainable flows that already exist.

These two levels of ecological tyranny require a detailed discussion of how particular politically chosen materials are threaded through society in institutional practices instead of discussing materials as if they were only ruled by equally interchangeable forms of abstract, timeless, market behavior or ruled by equally abstract conceptions of Marxist class warfare either.

On the contrary, it will be argued that evidence is already in: that there is nothing called abstract market behavior or generally abstract commodities and as a result nothing called abstract class behavior--there is raw material specific political and market behavior. However, I argue we can have abstract, general historical principles about particular materials (instead of abstract principles about abstract materials or abstract classes)--in how in their particulars they flow through human societies and interact with each other comparatively, historically and politically.

Methodologically, I use an inductive analysis of consumption instead of one based on mere philosophical assumptions of macro-reductionist class analysis or micro-reductionistic economic analysis.

It is based on aggregate case observations of many different particular consumptive flows and human behavior in relation to them as the basis of theory instead of using deductive, timeless theories of economics about philosophical constructs of abstract commodities, abstract human behavior, and abstract classes.

It is important to ground discussion of materials in empirical and historical case studies and fine-grained institutional analysis. Otherwise, we are substituting (or merely blending) a metaphysics of the abstract market or abstract classes for (and with) the metaphysics of the abstract environment without much empirical improvement. None of these three abstracts arguably exists materially beyond their conceptual use.

From this method, what is key is respecting that consumptive flows are particular, politicized flows that are unable to be reduced to any abstract analysis. It is an independent variable capable of making causal, dependent changes in both economics and politics.

There are two levels of these political flows.

Once a particular infrastructure is in place as a status quo and it meets market challengers in history in a free market, it first can use its status quo economic power to strangle market competition through its institutional structures and, secondly, it can use its political allies (i.e., use its political power).

This can explain why there is so much green technology available though little is applied. This topic is addressed later.

One of the difficulties of getting to sustainability is corrupt politics of a crony unrepresentative choice of material status quo, instead of a lack of technological and material options or instead of blaming consumers either. The issue is the gatekept and repressed lack of options--options that already exist, sometimes for generations.

This clientelistic point is typically ignored in economic theories based on assumed abstracts called commodities, markets, and classes despite a world full of many clear instances where materials are forms of political, repressive power against other materials, technologies, and social formations, instead of being abstract economic repression alone.

This power is expressed through its consumptive clientelism--how groups connected to such materials can dominate and sculpt flows of particular materials or dominate aggregate consumer use to forebear against economic/political change in certain consumer use categories (over other choices).

This is an interscientific method to explore and to conceptualize how common political power aspects of consumption have filtered or winnowed human political economic choices of our varied biophysical environment of choices to political goals of secure clientelism and secure wealth forms--making them political infrastructures causing environmental degradation politically insulated from any path change.

This environmental indeterminist view argues materials can be integrated into social analysis in two levels: through at least 90 kinds of markets (or distinct "social use sets of materials" without any "abstract theory of markets" ever possible) where materials are in contention with each other only within a specific set for the same position of use, as well as (for a generality) through having common characteristics of how the politics of hegemonic versus subaltern social relationships are reproduced or altered in socio/material conflict with each other in these sets. This merges competitive human agency and structural perspectives effortlessly.

Both Smithian or Marxist views abstract to inconsequentiality actual historical cases of singular material flows and their changes: one of them instills in the believer a social philosophy of abstract, fair, equilibrium-based, depoliticized commodities and their market relations; the other instills in the believer a social philosophy of equally abstract, unfair, inequitable class conflict of ownership relations of abstract wealth. Both ignore that once singular materials are historically established in use, they are a form of clientelistic power, hardly entirely a fair market phenomenon and hardly entirely an unfair repressive power. It is in the middle: a form of guided representativeness or unrepresentativeness in material selection to achieve consumptive ambivalence with repression of options simultaneously.

Typically, we are offered a pabulum of "just so" philosophical stories attempting to describe all commodities and economic behavior from the safe distance of mathematical economics. This distant gaze is connected closely with morality tales about the godlike neutrality of the supposed blind justice (or injustice) of the market when it may only be nearsightedness and blurred vision from the lack of experimental observational methods in approaching commodities and consumption without the abstract filters of Smithian economic preconceptions or Marxist class conflict.

Instead, real commodity histories are unpleasant to witness because so much interest-based politics (for all social interests) goes on clearly around certain commodities though people tend to look away analytically from the political sociological aspects of particular raw material flows. We are generally sold only a clean, abstracted, well-packaged casing of the final product whether sausages, laws, or economic ideologies in relation to “commodities” or the grand terms “the environment,” “the economy,” and “the origins of power.”

I argue that peeking in the kitchen for the recipe of specific material policy can contradict many ideas of neutral economics or Marxist thought--while improving them both. It can challenge the Smith-inspired functional theory of the “greater good” served in certain material policy by explicitly noting whom it serves more than others in organizations and consumers alike in clientelistic fashion against other options, as well it can improve preconceptions about Marxist inspired forms of “alienation” beyond the mere work site to how consumers and others are alienated from sustainability by others’ non-local unoptimal material choices imposed upon them. It can merge both economic traditions to analyze politicized consumptive infrastructures.

Many people, technologies, materials and ideas are conveniently put out of the way to have stable regimes of political raw material flows that define themselves as ‘sane,’ ‘normal,’ or ‘neutral outcomes’--that however depend on their hegemonic power by processing, creating, and managing to label and to marginalize material and technological heretics to keep particular durable market hegemonies of ideologies and materials in place as legitimate powers. Alternatives exist (in thought and material practices) though they are conveniently no where to be seen or no where to be discussed to maintain the power/knowledge of commodity choice.

The case of corrupt petroleum raw material regimes against its working energy alternatives and the case of the equally corrupt ‘tree paper regime’ against hemp are politicized discursive, material-institutional practices (with their expected hegemonic power to create or ban heretics institutionally to survive, instead of its power based on claims of ‘market success’) and are very clear politicized infrastructures for example.

I will introduce five interrelated terms to reorient our ideas of consumption to capture the political and organizational alliance aspects of material flows. The five are [1] ‘consumptive infrastructure,’ [2] an environmental definition of ‘the state’ as a contentious regime of political material flows, [3] ‘raw material substrates,’ [4] ‘raw material substrate sets’ and [5] ‘raw material regimes.’ These are the bare minimum for understanding our ecological tyranny and how to change it.

[1] Consumptive Infrastructure

The first term I propose is ‘consumptive infrastructure’ because it is a methodological corrective to economic reductionist analysis of consumer behavior or firm behavior as universally and simply atomistic, anomic, and as individuals following economic rationales among abstract commodities. I prefer this term “consumptive infrastructure” more than consumptive flow because it is a wider term that includes consumptive flow. The wider concentration here is on the dual 'institutional and built environment'-to-consumptive flow that is infrastructural: the durable chosen technical infrastructures, material flows, and politicized institutional practices combined. All are variables that sculpt the consumptive flows, and are more influential and more interesting instead of the flow by itself. An overconcentration on the consumptive flow misses these three interactive issues of durable social issues sculpting all consumptive flows.

There is already much on politicized technical infrastructures though it is required noting that technical frameworks lock to particular material handling flows instead of manipulating abstract materials. They are an artistic hybrid, a particular technical/material relationship interacting as a single infrastructure, instead of any sense of there being an abstract infrastructure or any sense we can discuss technology or materials respectively as separate.

[2] An Environmental Definition of 'The State' as a Contentious Regime of Political Material Flows

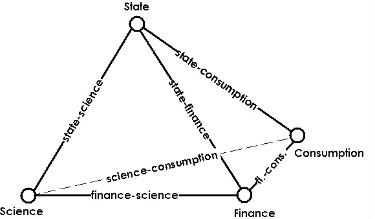

Keeping a political consumptive infrastructure perspective in mind, and seeing the graph above as a trellis to be filled by particular case studies and their variables, there are many other positional sites than simply the state institutions’ legal approval and applied science institutional practices that manipulate consumption and its power/knowledge/commodity choice relationships.

Particular consumptive infrastructures require jury-rigging in many other different positional venues as a common institutional alliance to get a raw material substrate to ‘work’ for some interest(s) (plural) as an imposed political consumptive infrastructure.

Four cross-cultural, strategic positional sites in political consumptive infrastructural analysis are offered: [1] the particular formal institutional and formal policy orientations of the state and their material/technical/infrastructural practices, [2] of science and their material/technical/infrastructural practices, [3] of consumptive organizations (corporations, co-operatives, community gardens, etc. all would fit the positional issue) and their (different) material/technical/infrastructural preferences, and [4] of financial organizations (corporations, co-operative lending banks, private banks, Islamic banks, state banks, etc.,--all would fit the positional issue and tweak the politics of the institutional power/knowledge/commodity choice differently) and their material/technical/infrastructural preferences. These four positional areas of any society work either in allied unison or in contention in constructing the material, technical, and infrastructural particularities of consumption.

In this alliance, a shared material alliance and a shared ideological alliance can flow and interact through these sites of potential political contention as an informal alliance to hold or to smooth the same policy with regard to certain materials over others. Originally, the woolsack was placed in the English House of Lords by the English king so the “separate” debates over financial policy would keep in mind what the king wanted: the defense and enhancement of his preferred financial instrument and a large portion of his budget at the time: the English woolen raw material economy. Political contention is manifested over exactly what type of formal institutions and formal policies, practices, and material/technical preferences appear as a regime in these ‘contentious, empty positions’ of state, science, consumption, and finance in societies--with the issue being over what raw materials these institutions support and discuss (or leave voiceless and deny) in their administration over aggregate others.

For sustainability interests, comparable evaluations can be made. These political consumptive infrastructures can either be clientelistic and unrepresentative or representative enfranchised varieties with democratized input on materials and technologies. Sustainability requires demotion of material and technical core areas of private political consumptive clientelism. These consumptive evaluations are based on how publicly representative or responsive (or unrepresentative or repressively clientelistic) the state, science, finance, and consumptive organizations are discursively and materially with respect to material, technical, and institutional practices of commodities and their choices.

One can empirically research both physical issues clientelism and democracy/representation (degree of externalities) associated with particular material choices and the types of institutional practices (from repression to participation) involved in formulating materials/technology policy as well as discourse analysis of the productions of these institutions compared and evaluated for what is voiced and what is left voiceless. This repression or reflectivity is the difference of degree the populace at large are consulted or are enfranchised in different institutional practices to provide feedback against unsustainable developmental potentials built from alliances of unrepresentative consumptive choice, discourses, and institutional decisions across the “SSFC” (state, science, finance, and consumptive organizations in a particular material case).

This takes views of commodities away from mostly economic reductionist and micro-reductionist analysis into a view of a planned and implemented political infrastructure in certain materials and technologies, protected and sponsored against challengers as a form of unrepresentative clientelism or as a more representative sense of policies of wider consumptive choices toward sustainability.

By following the commodity or material choice in question (and what institutional practices and decision frameworks of material regime led to the choices of policy,) this is really materialism instead of the philosophical materialism of Marx--limited artificially to analyze only one point of ownership (the consumptive position) and limited by his putting analysis in an entirely philosophical binary inherited from Hegel instead of a binary even materially demonstrated.

Cases of how materials are threaded through or hamstrung across these four main positional sites become a common research interest. The same material and organizational support is knitted through the whole consumptive infrastructure.

This is the first environmental perspective on defining ‘the state’ as a changing series of biased (or representative) consumptive alliance and clientelism organizations stretched between formal state institutions, scientific institutions, consumptive institutions, and financial institutions in their material practices and policy choices of materials, technologies, and infrastructural investments.

Either representative political alliances (via more plural democratic inputs on material choices about evaluating externalities) or unrepresentative political alliances (biased/hegemonic and degradative) would use the same four positional areas of state institutions, applied science, consumptive organizations and finance to network together versions and visions in certain materials through formal policies.

The stories of native autonomous amaranth (and its planting opposition in South America by the wheat-growing Spanish conquistadors interested in an alienated and clientelistic peasantry), aspartame, U.S./U.K. water fluoridation (while all of the major Western European countries reject it on health and ethical grounds), lead additives in gasoline, or genetically modified crop introductions can familiarize the reader with how various systemic power biases become a political regime first (not an economic regime first) that is generated out of certain institutional practices through their organizations’ discourses and choices of materials over aggregate populations without market demand. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) and its ‘update’ by Karen Steingraber, Living Downstream (1997) both are about the institutionalization of biased choices of herbicides/pesticides materials from certain military-institutional and supply-side choices first instead of consumer demand--and the discourse creations and cultural defamations in defense of critique, as mystifications generated by powerful institutional actors. Both books are an excellent (re)introduction to orient ourselves to political consumptive infrastructures.

It is hardly my intention to imply that only certain materials exhibit political consumptive infrastructures.

I only imply here that these written treatments recommended above are clearer than others about data showing the general phenomena of political consumptive infrastructures as built from alliances of institutional practices first imposed instead of derived from markets and ownership first and later leading to institutionalization. Marx who turned Hegel on his head has to be turned on his head once more to avoid his presumption of our economics instituting a ‘superstructure’ instead of the more demonstrable ‘superstructure’ causing (and changing over time) and defending ownership patterns as political alliances that change over time as well. This is closer to the historical record instead of one causing the other or visa versa as a timeless statement.

Sometimes opposed, sometimes allied, political and economic power require being historically specified in certain cases instead of defended philosophically by timeless foundation statements as Marx attempted to argue with causality always going one way of economics causing politics in the abstract. Sometimes politics causes economics, and any pattern of their interactions are always in particular material alliances versus other organizational forms and material choices as the warfare medium: different versions of clientelism against others, some more representative than others. Sometimes these clientelisms are rejected wholesale.

To rephrase Marx, there are six types of alienation involved in consumptive materials.

1) Instead of merely the worker being alienated from the object or the result of his production, whole societies can be alienated in material issues by small powerful material regimes of a few people with political support of major institutions for their material choice; the consumer is alienated from the object or the result of his consumption because of its externalities, and the consumer is alienated from their choice of materials in a gatekept and winnowed form of supply side politics as it gets larger and moves against demand’s interests of consumption. This is the principle of politicized ‘supply versus demand’ as scale increases that is discussed elsewhere.

2) Instead of merely alienation arising inside productive activity itself, it is hardly limited to productive activity. There is nothing categorically special about productive activity that shows more alienation than other forms of political unrepresentation down the whole politicized consumptive infrastructure and its institutional alliances when oriented toward alienation/clientelism instead of representation. Alienation at root is hardly an ‘economic’ issue; it is a political issue across many different institutional sites either oriented better toward representation and sustainability or oriented poorly toward clientelism/alienation and unsustainability. There is nothing particular special or unique that Marx identified in his production node of alienation. It was one of many political-organizational nodes in a raw material consumptive path of environmental flows which Marx falsely framed as ‘economic’ because of his reductionistic intent to analyze one particular venue of political conflict and extrapolate it to the rest of society’s institutional forms which can instead show a variety of different orientations of representation or clientelism/alienation at the same moment potentially. Instead of thus a class warfare based reductionism on one production site in the larger institutionalized consumer flow of materials, there is an organizational design warfare occurring throughout all positions of the consumptive path over the degree of representation and sustainability of geographic self-interest of the organizational form, or the degree of unrepresentation, clientelism, gatekeeping, alienation and unsustainability in the organizational form that ignores geographic self-interest.

3) Instead of because of external labor, man externalizes himself (Self-alienation), it depends on how representative are the organizational frameworks in which labor and the whole gamut of consumption takes place--some organizations representative than clientelistic/alienating others. Yes, Marx identified a form of unrepresentative clientelism as a form of self-alienation though there is a difference in representative, mutually beneficial clientelism and unrepresentative clientelism that is alienation. All clientelism is not alienation. Some is. Some is not.

4) Instead of people alienating themselves from each other only through external labor, the alienation is on the level of choices (what kinds instead of all)--some more unrepresentative and unsustainable and some more representative and sustainable. Thus instead of categorically timeless, the alienation is due to external material choices and technical productions choices that are out of sync with particular ecological and sustainable ‘species-being’ situations which would either lead to a mutual lack of alienation versus mutual self-alienation between people. This is an alienation of all species life: an alienation of a person from himself/herself, an alienation of a person from other people, and an alienation of a person's particular ecological self-interest, i.e., an alienation of their interest in being a member of a particular region in which they encourage its durability or undermine it through the choices of materials and technology optimized for their ecological self-interest. Additionally, there is thus a wider social and cross-species geographic alienation, shared across species in an area, instead of only Marx’s individual creativity is what is marginalized in particular state/urbanist supply-side consolidations. Regions are alienated under unsustainability. These unrepresentative state “SSFC” relationships lead to unsustainability and thus alienate particular regions from political voice and material, technical, and organizational optimal choice--whether urban or rural areas or both--in the rush to integrate only clientelistic consumers politically into clientelistic/alienating choices of materials, technologies, and organizations that support an environmentally and consumptively alienating regime built from themselves as individualized, alienated consumers while demoting politically and economically the institutionally durable forms of geographic representation of consumption that would represent all species being in a particular region, instead of alienate all species beings in a particular region.

5) Thus, it is hardly ‘capitalism’ as a strange abstract that is causing the difficulty--an abstract derived from Marx’s reductionism gaming the system of his analysis instead of a wider materialism than productionism that would show the difficulties with alienation/clientelism are a society-wide embedded politicized raw material regime of alientating and clientelistic unrepresentative materials, technologies, and organizational forms pressuring people into alienating/clientelistic positions of others choices--instead of within external material, technological and organizational forms that would be involved with more representing-clientelistic material relationships. It is a cross-organizational political framework instead of an economic one at root holding people in alienation/clientelism. It is a political one of poor social choices biased toward supply versus demand, unsustainability, and self-destruction in the long term.

6) Thus the politics of unrepresentative state-elite-led environmental degradation and their material, technical, and organizational pressures to integrate people via alienation/clientelism versus a building movement for environmental improvement through more geographically-sensitive optimal choices of material, technical, and organizationally representative clientelism have been the core ‘green’ dynamic of world history. The whole dynamic is green versus gray in world history. I challenge the whole Eurocentric modernist British economics/Marxist idea of different eras. Instead, different ‘eras’ show the same dynamic, past or present, at ever-wider scales of the same process. A second reductionism is the historical misspecification that Marx and all modernists perpetrated when they talked of ‘capitalism’ supposedly replacing ‘feudalism.’ Instead modernists were talking merely of the early stages of a larger ‘feudalization’ (or privatization--a state-supported private material, technical, and organizational clientelism and alienation) extending larger than previous forms.

[3] Raw Material Substrates and [4] Raw Material Substrate Sets'

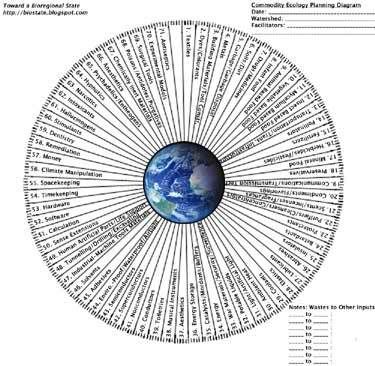

Raw material substrates are the (estimated) 90 general positional frameworks of consumption for different social uses. They are empty social positions of consumptive use, chosen to be filled by a particular raw material. Raw material substrate sets are the potential gamut of choices of raw materials for the same social positional utilities of consumption into which many various consumptive items would ‘fit,’ each of them with different physical/biological characteristics that would influence the ‘tweak’ or look of various social aspects of consumption.

A case example of a raw material substrate set is textiles, in particular looking at comparisons across cotton, wool, and silk which is what Marx should have done as a materialist instead of adopting British falsely abstract ideas about commodities in general. Despite being the same presumed abstract textile industry, the three materials have radically different (and historically durable) social morphologies, social stratification regimes (different levels of proletarianized work organization), organizational sociologies, technological comportments and scale potentials directly caused by different biophysical and supply characteristics of the chosen thread in how this affects urban industrialization differences, proletarianization differences, and political capital ownership and control differences.

Every raw material of human use can potentially hold a raw material substrate position, in set-based competition. Any of them could be chosen for a consumptive infrastructure. For example, we have the raw material substrate set position for textiles, the raw material substrate set position for agricultural staples and the raw material substrate set position for building materials.

[larger image]

Others would be the raw material substrate position set for energy--a society’s set-based choices. Coal, oil, wood, solar power, nuclear power, compressed air car engines (clean air in and clean air out--no pollution or combustion; mass manufactured in India from 2007), or split-water hydrogen power (with no waste or pollution except the same water once more, Japanese manufacturers are ready; Philippine inventors like Dinkel are repressed; American inventors like Stan Meyer ended up with international patents, though dead in a U.S. jail once he started to work on water engine conversions with a local automotive dealer.) All would all be considered contenders in the set for the same general position of raw material substrate choices(s) for energy supply.

As in the textiles excerpt above, each would tweak the position and organizational politics in the above four areas of ‘the state’ in their own case-specific direction. As such, each material in contention for the position of social use would be associated with various and different state, science, consumptive, and financial sponsorships, attempting to promote themselves and demote challengers politically and institutionally.

See this link for more discussion.

[5] Raw Material Regimes

Raw material regimes join all the above concepts. They are infrastructures of informal/formal pressures and simultaneously public/private political alliances used to institute select materials and interests over others along the raw material substrate path of institutional politics. A raw material regime is a secure informal consumptive administration framework that involves demoting other (or promoting/protecting) choices through three areas: formal institutions, formal policies, and informal political pressures.

Additional to these three areas of political institutional practices of materials, there are three infrastructural positional levels of any durably orchestrated raw material regime: institutionalization, legalization, and legitimation--suggesting both how they are durable or challenged and changed.

Institutionalization of a Raw Material Regime

Institutionalization of a raw material regime involves two distinct levels of social embeddedness of raw material use: (1) meso-organizational and macro-organizational habit (satisficing behaviors of firms, particularly (1.1) due to technological ‘built infrastructure’ investment in previous fixed capital requiring material flow deliveries in bulk to make the organization’s scale profitable and durable in this manner and (1.2) via the path of how technological manipulation typically is used at supply-side ideological scales as a strategy or excuse to fix specific material pre-choice capacities physically into dedicated machinery without capable of being adapted later to changing supply contexts. The infrastructure is built to require a certain material use, and that use in bulk as well. It only fits that material, hand in a glove.

(A counter example or exceptions that prove the supply side ideological rule would be infrastructures that can preserve choice like the ‘flex fuel’ engines in history that let the consumer decide the fuel instead of being decided upon by the engine makers beforehand: like the current Brazilian automotive industry, the early 20th century original multi-biofuel Diesel engines, or Paul Pantone’s GEET (Global Environmental Energy Technology) fuel processor that runs on any waste hydrocarbons though 80% water without any carbon exhaust and more oxygen extruded than came into the machine).

Either way--whether supply-side informed that removes choice or demand-side informed that preserves choice--all infrastructural investments institutionalize particular choices of raw material flow relationships specific to the technology or built environment at hand.

The second level of institutionalization of a raw material regime is (2) the micro-level aggregate consumer or individual habit. This is either the laborer’s or consumer’s ‘consumptive familiarity’ or symbolic association with the material, instead of a presumed daily-conducted search for material optimality in market relations.

These are the macro/meso and aggregate micro levels of institutionalization, respectively, working interactively in alliance or opposition depending on the case.

This enculturation of use is always of particular raw materials over others--associated with organizational and/or individual habit. This ‘habit’ side of use comes from satisficing behaviors in a raw material search strategy. Disagreeing with those who put economic habit in a residual category of “past, traditional” economic rationality, more modern day action is habitual instead of rational calculating than most would surmise.

Habit is arguably a far more important issue due to the larger-scale consumption of the present, in our consumptive infrastructures that calls forth more meso and macro institutional political pressures upon winnowing micro consumer choices, than in a supply-side politically marginalized past.

Since consumption, particularly on the individual level is so involved in ‘comfort’ issues, identity/status issues, ‘escapist’ issues, laziness, or satisfaction out of sheer habit, once consumption is institutionally ‘locked in’ then consumers in aggregate can have incredible connections to particular consumptive items, that facilitate in turn the justification of investment for more systemic consumptive administration (and politicized supply-side bias winnowing pressures) on the organizational habit level, and visa versa.

Habitual and identity-based consumers and technology that encourages only certain forms of material manipulation are something that breaks down the primary assumption of modernist economic epistemes: demoting past beliefs in the individual, autonomous, primarily-rational economic actors always looking for simply the cheapest commodity.

That is “rational” of course, though only one form of rationality, for the rationale why people consume particular things. There can be nothing called “irrational” consumption, only different rationales of consumption.

On the level of the individual (though aggregate) consumer, politicized consumptive infrastructures even though they are political economic administration frameworks are imbibed within thousands of individualized narratives about identity and personal comfort even if something once decided upon as part of an identity turns out to be highly carcinogenic later.

For instance is bread, the Christian ‘staff of life,’ going the way of this into a pyx of death through more knowledge about its dangerously high level of acrylamides?

Some may change their behaviors based on risk information, a rational response. Others may be mad at the information and pretend to ignore it--another quite “rational” response if the rationale is habit and comfort.

Of course, systemic powers rarely tell them about the product’s or material’s dangers that have been discovered, instead of keeping it secret.

Legalization of the Raw Material Regime

Legalization of the raw material regime refers to particular strategic political alliances with varying degrees of representation or unrepresentation (respectively, clientelism/alienation or institutionalization of choice) between government organizations, raw material procurers/suppliers, and consumers that are institutionalized from the level of the state into formal laws and formal institutions dealing with the raw material in question across the full raw material substrate path.

This can be for direct sponsorship (like an overt state monopoly) or an indirect sponsorship (like a protected private monopoly or hegemony that makes other consumptive options or challengers illegal thus enforcing by default a consumptive heresthetics and consumptive administration frameworks in the indirectly selected material); or alternatively, state legalization frameworks that expand and protect instead of contract consumer choices of materials in the consumptive set.

Legitimation of the Raw Material Regime

Legitimation of raw material regimes refers to open-ended contentious political and discursive processes of material support. It involves mobilizing cultural frameworks and discourse--talking about certain materials employing language, symbols, associations, ideas and emotions. In contentious political talk about a raw material regime, one will typically find this talk organizes itself along a differential of power: those that are interior to a raw material regime defending it versus those exterior to the raw material regime, with the latter being a plurality of different groups either fellow-traveling and/or mutually oppositional who experience its externality effects, and/or who would offer different materials for the position, or who wish to widen consumer choices.

Legitimation refers to cultural social-movement offensives against (or countermovement defenses for) a particular raw material substrate use. In the socialization around certain raw material flows, there are open-ended jockeying attempts to legitimate or delegitimate certain raw material regimes from current hegemonic locks on formal institutional and formal policy governmentality over the whole society.

Materials change proponents wait for certain political opportunities like any other social movement would; and raw material regime defenders act like any countermovements do: defending their materials through typical countermovement behaviors like biased and corrupt state power policing, state-sponsored vigilante action, and funding agent provocateurs.

However, publicity and propaganda can backfire from desired attempts to legitimate and can turn into self-delegitimation as well. Therefore institutional practices and strategies of silence or secrecy about the material practices as much as strategies of talk are crucial to legitimating a raw material regime down the raw material substrate path--via both institutional pronouncements and a lack thereof.

the data on carcinogen DDT led Rachel Carson to write the book Silent Spring (1962). This is one case example of the knowing institutionalization of physical risk by scientists as they simply maintained a code of silence to keep the public consumptively ambivalent. Their institutional job security along the raw material substrate path of the raw material regime of chlorinated carbon compounds (particularly DDT) kept them systemically in line. The material links of salaries as well can be considered in a form of raw material regime as well.

After Carson published, there was a huge corporate and government countermovement public relations attack on her to delegitimate and to discredit any listening consumers--instead of dealing with the toxics information--who wanted to pull away from the raw material regime around the novel toxic chlorinated herbicides and pesticides. However, chemical corporations hoped that already coddled consumers would go back into consumptive ambivalence with very little prodding. Thus the institutional silence around toxic chemicals as a response was another form of the silence in Silent Spring.

A third example of the use of silence along the raw material substrate path to maintain the raw material regime can be analyzed through the consumptive infrastructure of “fluorine”--a very electronegative and very small element and its compounds used in many institutional practices of materials choice despite its well known toxicity. In the United States the legal label of ‘fluorine’ actually means any number of different types of physical compounds each with differing toxicities that are put into water. Mostly, these fluorides in the United States were directly considered an expensive to remediate nuclear or industrial waste by-product seconds before they were put into the water supply and magically, through the alchemy of laws and certain institutional handling practices and allowances, turned into something somehow treated differently than the carcinogenic, mental-developmentally-damaging, neurotoxic, abortifacient, and skeletal fluorosis-causing industrial toxin that it is. All Western European countries have rejected fluoridated water on public health and medical ethics grounds combined. The U.K. and U.S. alone (with some of its allies like South Korea) legitimate this industrial toxin in their water as if they were unaware of the dangers.

They are aware, as noted in the book The Fluoride Deception. It’s a fluoride raw material regime with a great deal of strategic silence and co-ordination down the raw material substrate path--a well-documented, cross-institutional code of Mafia-like ‘ometra’ to ignore discussing the dangers of fluoride. The outcome is that many British and Americans are allowed to be poisoned by fluoride--cynically legitimated as a public health intervention and legitimated by individual-level habit and individual interpretation as well--a very solid raw material regime indeed.

Conclusion

One of the points of this discussion is to call the lie upon the economic idea that we live in a world of actual choices where ‘supply equals demand’ toward equitable models of markets without history, to call as a lie that the main conflicts are class oriented instead of consumptively oriented, and to call into question the fraud that we live in an ‘economic’ world instead of a politicized material flow based world based on domination or representation.

No where have we ever lived in a politically-neutered commodity situation in human history, and the politicized state-consumptive institutional practices issues of raw material regimes may be more extreme at present that ever due to the huge scale in many consumptive use positions.

Ecological Tyranny, or the Bioregional State

Furthermore, no where will we ever live in that de-statized, depoliticized and ahistorical situation with regards to commodities in general: it (and sustainability) will solely be a question of how representative or unrepresentative are these 90 social relations of commodity choices of materials. In other words, raw material choice is an institutional practice that can be representative and reflexive of physical, ecological and economic risk, or it can be involved in unrepresentative institutional practices and generate such risks, clientelism, and alienation unsustainably.

Instead, we live in a world of politically-manipulated consumption for ill or good. We have always lived in a world of this merged and administered socio/material consumptive power where various institutions have winnowed consumer choices well before consumers actually get to them for the interest of political economic elite clientelisms as a form of power, and where choices of social ideas and choices of material consumption can be constrained by the same institutionalized practices or opposed by them as well.

As mentioned above, the issue becomes less how romantically to ‘overthrow’ this mélange of power relations, as some sort of power relations will always be there.

The issue becomes what would sustainable, bioregional, participatory and democratic power, knowledge, and commodity institutional practices and choices look like organizationally instead of aristocratic, gatekept, clientelistic, and unrepresentative socio/material inducements and consumptive institutional pressures on consumers leading to environmental degradation?

Commodity choice as a phenomenon has been misspecified as an economic policy when it is a political, cultural, and ideological policy issue: do you want unsustainability or sustainability?

And many of these politicized material flows are ecological tyrannies destroying our health, ecology, and economies all at once.

The question is: what would representative consumption look like, institutionally speaking, that would demote the institutional practices of clientelistic and risk-facilitative aspects of consumptive choices? The answer is a a bioregional state can oppose these ecological tyrannies: a representative material framework of institutional practices in consumption, state, science, and finance instead of one that alienates and leads to unrepresentative clientelism and environmental degradation by ignoring the different optimums of ecological self-interests of people in different regions of the world.

It is up to us to identify what does allow people a certain liberation, voice, choice and human action toward sustainability. Sustainability is a democratic and representative framework of locally optimal consumption in all its variations, instead of “pseudo-public” private infrastructures or consolidated “nationalized” infrastructures both biased to create environmental degradation, ignore citizen outcry, and impose physical risk--the latter as the “pseudo-opposition” from Marx-Leninism that self-limits the whole analysis and fails to note the specific material practices of particular flows is wider than organizational ownership politics?

And it is up to us to have a way to analyze and to evaluate the root issue--the ecological tyranny of these unrepresentative politicized consumptive infrastructures--toward a sustainability of more locally optimal material and technical choices.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home